"Think Again" Highlights and Notes

🚀 My summary of this in a few sentences

Think Again is a book by Adam Grant that explores the importance of being open to change and rethinking our beliefs and assumptions. The book argues that being open to new ideas and considering different perspectives can lead to better decision-making, improved relationships, and greater success. To do this, Grant suggests that we need to cultivate a growth mindset, practice intellectual humility, and engage in regular self-reflection.

🎨 My impressions

It had the same vibes as the book "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by another author.

🤷🏽♂️ Who Should Read It?

Everyone. People who think they are absolutely right about everything and people who think they are absolutely wrong about everything, and everyone in between.

🔍 How I discovered it

I saw it as a recommendation while I was looking up "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman.

✍️ Top Quotes

We all have notions of who we want to be and how we hope to lead our lives. They’re not limited to careers; from an early age, we develop ideas about where we’ll live, which school we’ll attend, what kind of person we’ll marry, and how many kids we’ll have. These images can inspire us to set bolder goals and guide us toward a path to achieve them. The danger of these plans is that they can give us tunnel vision, blinding us to alternative possibilities. We don’t know how time and circumstances will change what we want and even who we want to be, and locking our life GPS onto a single target can give us the right directions to the wrong destination.

📒 Archive

Remaining Highlights and annotations on Think Again

Highlights

Prologue

We often readily change ourselves throughout the years on some things and laugh at people who stay in the past, but we are reluctant to change opinions that are equally as old and need careful consideration of review

Rethinking isn’t a struggle in every part of our lives. When it comes to our possessions, we update with fervor. We refresh our wardrobes when they go out of style and renovate our kitchens when they’re no longer in vogue. When it comes to our knowledge and opinions, though, we tend to stick to our guns. Psychologists call this seizing and freezing. We favor the comfort of conviction over the discomfort of doubt, and we let our beliefs get brittle long before our bones. We laugh at people who still use Windows 95, yet we still cling to opinions that we formed in 1995. We listen to views that make us feel good, instead of ideas that make us think hard.

Being in scientist mode, means you're always challenging your ideas about anything and never letting it become an absolutism or ideology

When we’re in scientist mode, we refuse to let our ideas become ideologies. We don’t start with answers or solutions; we lead with questions and puzzles. We don’t preach from intuition; we teach from evidence. We don’t just have healthy skepticism about other people’s arguments; we dare to disagree with our own arguments.

Thinking like a scientist involves more than just reacting with an open mind. It means being actively open-minded. It requires searching for reasons why we might be wrong—not for reasons why we must be right—and revising our views based on what we learn

Some people stick to preacher mode, refusing to change because it makes them lose face or come off as a hypocrite. But in science, that is exactly what you'll have to sacrifice to gain wisdom. Through doing things differently can you discover different things or further strengthen your logic

🎸 DON’T STOP UNBELIEVING

Something to try out is to think about things that you don't know and list them. You can potentially learn bit by bit about it but as long as it is externalized, you'll have a more concrete version of things you think you are ignorant about.

We should all be able to make a long list of areas where we’re ignorant

The overconfidence cycle is basically a time when you refuse any new idea because you're overly confident that what you think is true is irrefutable

Scientific thinking favors humility over pride, doubt over certainty, curiosity over closure. When we shift out of scientist mode, the rethinking cycle breaks down, giving way to an overconfidence cycle.

If we’re preaching, we can’t see gaps in our knowledge: we believe we’ve already found the truth.

Pride leads to confirmation and desirability bias, biases which steer us away from actually more logically sound and cogent thinking cycles and lock us into that thinking cycle.

Pride breeds conviction rather than doubt, which makes us prosecutors: we might be laser-focused on changing other people’s minds, but ours is set in stone. That launches us into confirmation bias and desirability bias. We become politicians, ignoring or dismissing whatever doesn’t win the favor of our constituents—our parents, our bosses, or the high school classmates we’re still trying to impress. We become so busy putting on a show that the truth gets relegated to a backstage seat, and the resulting validation can make us arrogant

Our convictions can lock us in prisons of our own making. The solution is not to decelerate our thinking—it’s to accelerate our rethinking. That’s what resurrected Apple from the brink of bankruptcy to become the world’s most valuable company.

The feeling of safety in pride is because we feel often safe in beliefs we've held long term, so it helps to have some common ground or some old views that are reinforced while introducing new ways of thinking, rather than do a complete 180 on them.

Research shows that when people are resistant to change, it helps to reinforce what will stay the same. Visions for change are more compelling when they include visions of continuity. Although our strategy might evolve, our identity will endure.

👌🏽 Finding the Sweet Spot of Confidence

Confidence in a domain is not necessarily proportional to competence in that domain

In theory, confidence and competence go hand in hand. In practice, they often diverge. You can see it when people rate their own leadership skills and are also evaluated by their colleagues, supervisors, or subordinates. In a meta-analysis of ninety-five studies involving over a hundred thousand people, women typically underestimated their leadership skills, while men overestimated their skills

Low confidence in a domain even though one has high competence in it leads to impostor syndrome. You could have all the best qualifications and accolades to prove you're "the best" but for some reason, you may feel like an out-of-place fake that doesn't deserve it.

The opposite of armchair quarterback syndrome is impostor syndrome, where competence exceeds confidence. Think of the people you know who believe that they don’t deserve their success. They’re genuinely unaware of just how intelligent, creative, or charming they are, and no matter how hard you try, you can’t get them to rethink their views

🤡 The ignorance of arrogance

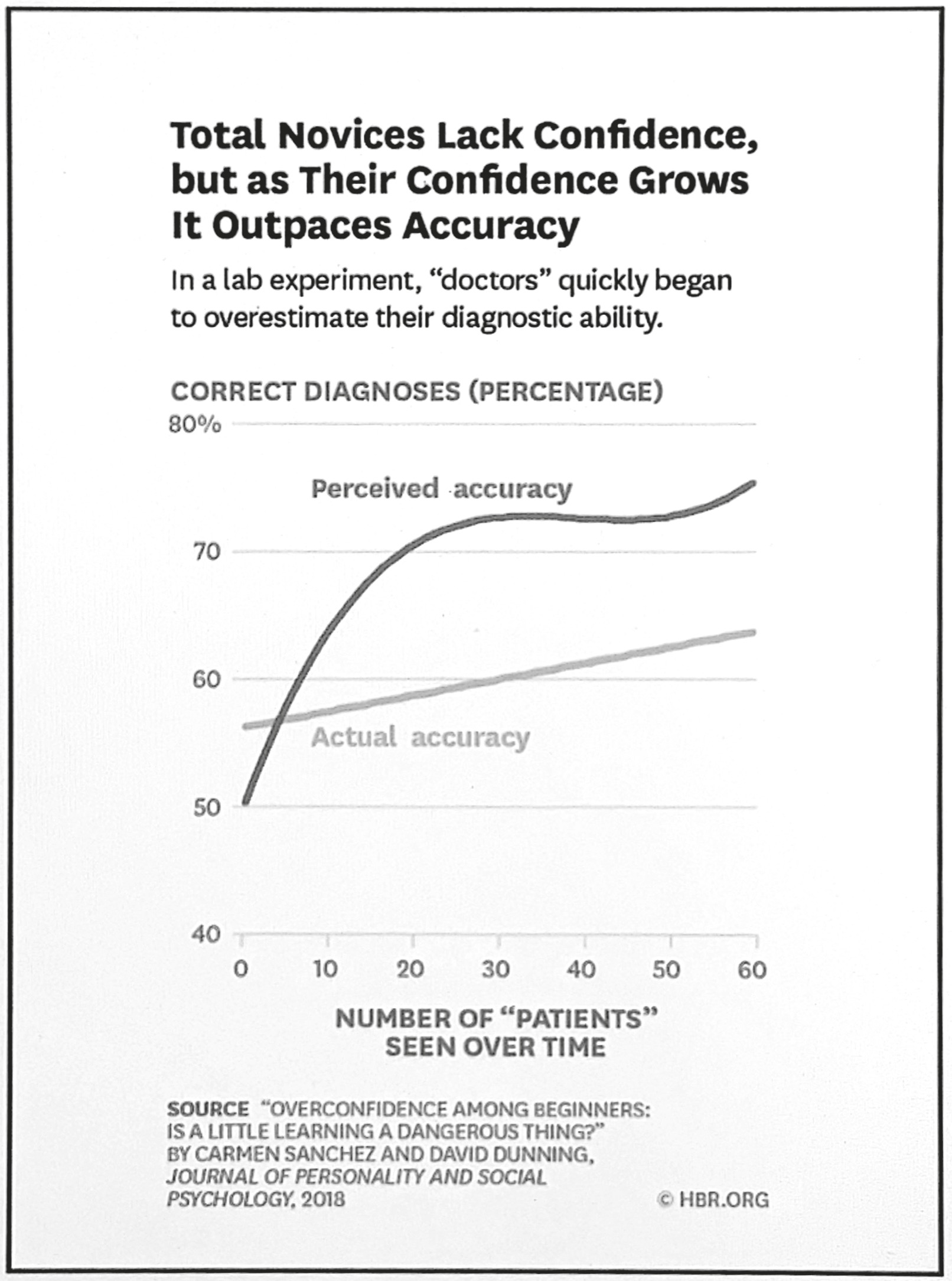

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a phenomenon that describes that the less intelligence someone has about a domain, the more they are likely to overestimate their intelligence in the said domain

The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club.

In the original Dunning-Kruger studies, people who scored the lowest on tests of logical reasoning, grammar, and sense of humor had the most inflated opinions of their skills. On average, they believed they did better than 62 percent of their peers, but in reality outperformed only 12 percent of them. The less intelligent we are in a particular domain, the more we seem to overestimate our actual intelligence in that domain

🗻 STRANDED AT THE SUMMIT OF MOUNT STUPID

👩🏻⚖️We cannot judge excellence if we don't have the knowledge and skills required to have that excellence. So we cannot just randomly assume other people are excellent at what they do or feel bad for even assuming they are excellent.

🕹️ Experience is not the same as expertise. You could be doing the same thing for decades but still not have the skillset as someone who has took time to rethink and re-approach their own skills

We’re all novices at many things, but we’re not always blind to that fact. We tend to overestimate ourselves on desirable skills, like the ability to carry on a riveting conversation. We’re also prone to overconfidence in situations where it’s easy to confuse experience for expertise, like driving, typing, trivia, and managing emotions. Yet we underestimate ourselves when we can easily recognize that we lack experience—like painting, driving a race car, and rapidly reciting the alphabet backward

😌 In many domains of our lives, when we get a bit of knowledge, we become self-assured but it doesn't mean we are actually knowledgeable. That's one sign we have reached the top of Mount Stupid but have not even started the climb on mount greatness.

It’s when we progress from novice to amateur that we become overconfident. A bit of knowledge can be a dangerous thing. In too many domains of our lives, we never gain enough expertise to question our opinions or discover what we don’t know. We have just enough information to feel self-assured about making pronouncements and passing judgment, failing to realize that we’ve climbed to the top of Mount Stupid without making it over to the other side

👧🏼 WHAT GOLDILOCKS GOT WRONG

🙇🏻 Admitting that you don't know is the first step on the path to knowledge.

Confident humility doesn’t just open our minds to rethinking—it improves the quality of our rethinking. In college and graduate school, students who are willing to revise their beliefs get higher grades than their peers. In high school, students who admit when they don’t know something are rated by teachers as learning more effectively and by peers as contributing more to their teams. At the end of the academic year, they have significantly higher math grades than their more self-assured peers. Instead of just assuming they’ve mastered the material, they quiz themselves to test their understanding

🤨 THE BENEFITS OF DOUBT

😅 While having impostor syndrome could be debilitating, a small dose of it makes us hunger for learning and improving from what we already are.

impostor thoughts can motivate us to work smarter. When we don’t believe we’re going to win, we have nothing to lose by rethinking our strategy. Remember that total beginners don’t fall victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect. Feeling like an impostor puts us in a beginner’s mindset, leading us to question assumptions that others have taken for granted.

🎬 Action breeds confidence, not the other way around. Don't wait for confidence to arrive.

We don’t have to wait for our confidence to rise to achieve challenging goals. We can build it through achieving challenging goals

𝍃 Maintain your doubts so you don't get blind-sighted by overconfidence

Great thinkers don’t harbor doubts because they’re impostors. They maintain doubts because they know we’re all partially blind and they’re committed to improving their sight. They don’t boast about how much they know; they marvel at how little they understand. They’re aware that each answer raises new questions, and the quest for knowledge is never finished

😶🌫️ The Thrill of Not Believing Everything You Think

⭐️ Your value system determines the core of what you believe, not your belief system.

Who you are should be a question of what you value, not what you believe. Values are your core principles in life—they might be excellence and generosity, freedom and fairness, or security and integrity. Basing your identity on these kinds of principles enables you to remain open-minded about the best ways to advance them. You want the doctor whose identity is protecting health, the teacher whose identity is helping students learn, and the police chief whose identity is promoting safety and justice. When they define themselves by values rather than opinions, they buy themselves the flexibility to update their practices in light of new evidence.

👽THE YODA EFFECT

Learning from mistakes, being wrong, and learning, even more, because of it, is a reward in itself.

Accept the fact that you’re going to be wrong,” Jean-Pierre advises. “Try to disprove yourself. When you’re wrong, it’s not something to be depressed about. Say, ‘Hey, I discovered something!

MISTAKES WERE MADE . . . MOST LIKELY BY ME

🥲 Admitting mistakes is rewarding in its pain so long as you realize some of this pain is essential

Being wrong won’t always be joyful. The path to embracing mistakes is full of painful moments, and we handle those moments better when we remember they’re essential for progress. But if we can’t learn to find occasional glee in discovering we were wrong, it will be awfully hard to get anything right.

Make your opinion falsifiable with conditions laid out for how it could reach the state where your opinion would fail to be held in an argument. Use this to not only hone your opinion but to see where your thinking traps/mistakes appear in your held opinion.

When you form an opinion, ask yourself what would have to happen to prove it false. Then keep track of your views so you can see when you were right, when you were wrong, and how your thinking has evolved. “I started out just wanting to prove myself,” Jean-Pierre says. “Now I want to improve myself—to see how good I can get.”

😇 The Good Fight Club

Relationship conflict is unproductive, but task conflict is necessary.

there’s evidence that when teams experience moderate task conflict early on, they generate more original ideas in Chinese technology companies, innovate more in Dutch delivery services, and make better decisions in American hospitals

As one research team concluded, “The absence of conflict is not harmony, it’s apathy.”

Task conflict can be constructive when it brings diversity of thought, preventing us from getting trapped in overconfidence cycles. It can help us stay humble, surface doubts, and make us curious about what we might be missing. That can lead us to think again, moving us closer to the truth without damaging our relationships

Kids whose parents clash constructively feel more emotionally safe in elementary school, and over the next few years they actually demonstrate more helpfulness and compassion toward their classmates.

🐸 THE PLIGHT OF THE PEOPLE PLEASER

To be a good rethinker, surround yourself with a challenge network, not a support network

We learn more from people who challenge our thought process than those who affirm our conclusions. Strong leaders engage their critics and make themselves stronger. Weak leaders silence their critics and make themselves weaker. This reaction isn’t limited to people in power. Although we might be on board with the principle, in practice we often miss out on the value of a challenge network.

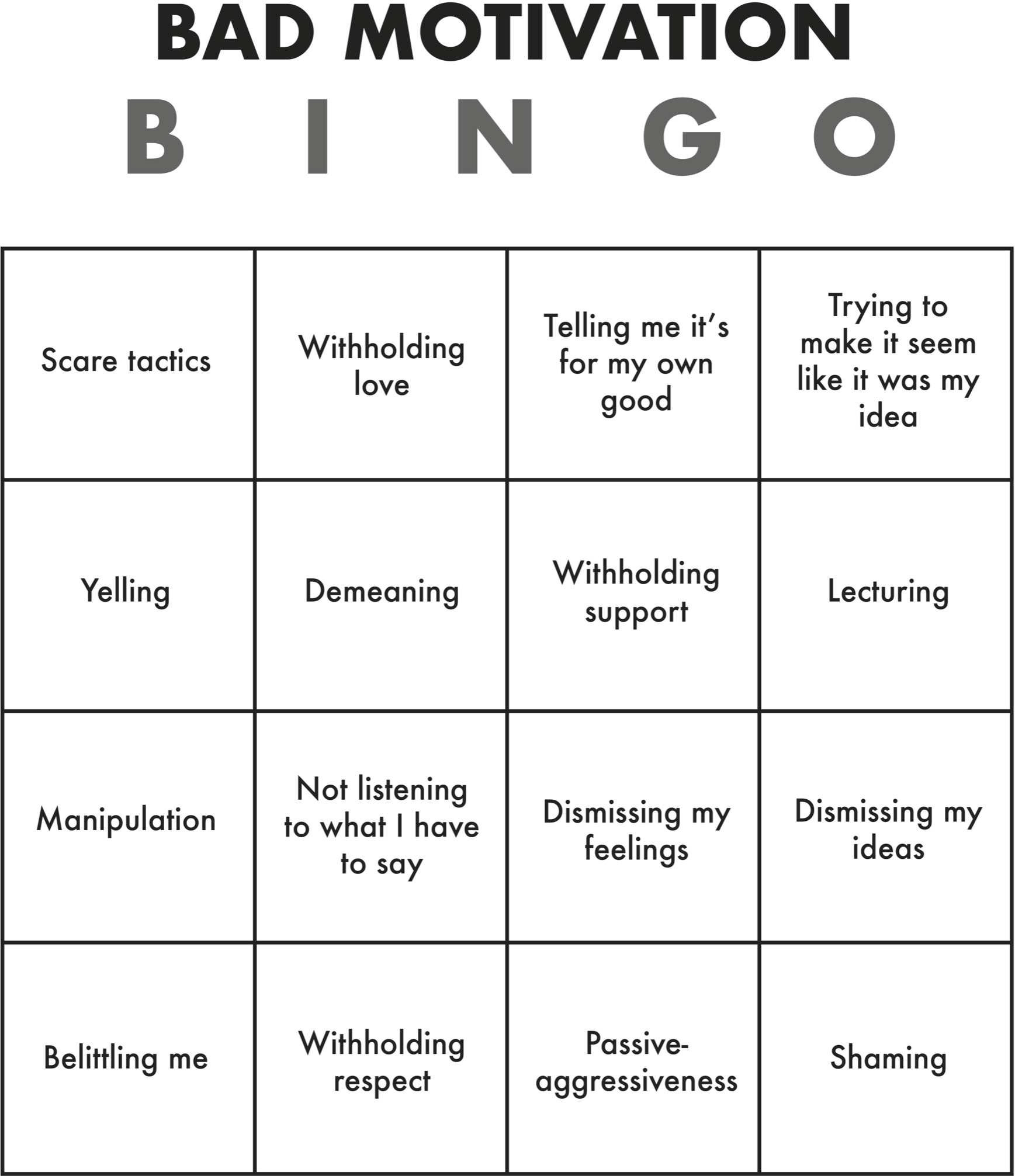

👨🏻💼 Be careful about giving tough feedback, because it may be more counterproductive to the effect you want to achieve.

In one experiment, when people were criticized rather than praised by a partner, they were over four times more likely to request a new partner. Across a range of workplaces, when employees received tough feedback from colleagues, their default response was to avoid those coworkers or drop them from their networks altogether—and their performance suffered over the following year.

GETTING HOT WITHOUT GETTING MAD

Frame your argument by saying "can we debate" before you start a dispute. This probably reduces hostility when the actual dispute starts.

Experiments show that simply framing a dispute as a debate rather than as a disagreement signals that you’re receptive to considering dissenting opinions and changing your mind, which in turn motivates the other person to share more information with you. A disagreement feels personal and potentially hostile; we expect a debate to be about ideas, not emotions. Starting a disagreement by asking, “Can we debate?” sends a message that you want to think like a scientist, not a preacher or a prosecutor—and encourages the other person to think that way, too.

🔍 Use "how would this work in practice" in your arguments rather than saying "why". The former emphasizes something concrete and practical to be laid out in the argument whereas the latter causes the opponent to double down on their emotional convictions towards that opinion.

When they argued about the propeller, the Wright brothers were making a common mistake. Each was preaching about why he was right and why the other was wrong. When we argue about why, we run the risk of becoming emotionally attached to our positions and dismissive of the other side’s. We’re more likely to have a good fight if we argue about how.

When social scientists asked people why they favor particular policies on taxes, health care, or nuclear sanctions, they often doubled down on their convictions. Asking people to explain how those policies would work in practice—or how they’d explain them to an expert—activated a rethinking cycle. They noticed gaps in their knowledge, doubted their conclusions, and became less extreme; they were now more curious about alternative options.

How encourages a "scientific thinker" mindset, allowing humility to come of the discussion

Psychologists find that many of us are vulnerable to an illusion of explanatory depth. Take everyday objects like a bicycle, a piano, or earbuds: how well do you understand them?

🤝 THE SCIENCE OF THE DEAL

🤬 Don't overwhelm your opponent with arguments, give the opponent space to think so that they are more likely to come to some common ground with you.

“A logic bully,” Jamie repeated. “You just overwhelmed me with rational arguments, and I don’t agree with them, but I can’t fight back.”

At first I was delighted by the label. It felt like a solid description of one of my roles as a social scientist: to win debates with the best data. Then Jamie explained that my approach wasn’t actually helpful. The more forcefully I argued, the more she dug in her heels. Suddenly I realized I had instigated that same kind of resistance many times before.

🕺🏻 A good debate is not a power struggle, it is a dance. Don't lead too hard.

A good debate is not a war. It’s not even a tug-of-war, where you can drag your opponent to your side if you pull hard enough on the rope. It’s more like a dance that hasn’t been choreographed, negotiated with a partner who has a different set of steps in mind. If you try too hard to lead, your partner will resist. If you can adapt your moves to hers, and get her to do the same, you’re more likely to end up in rhythm.

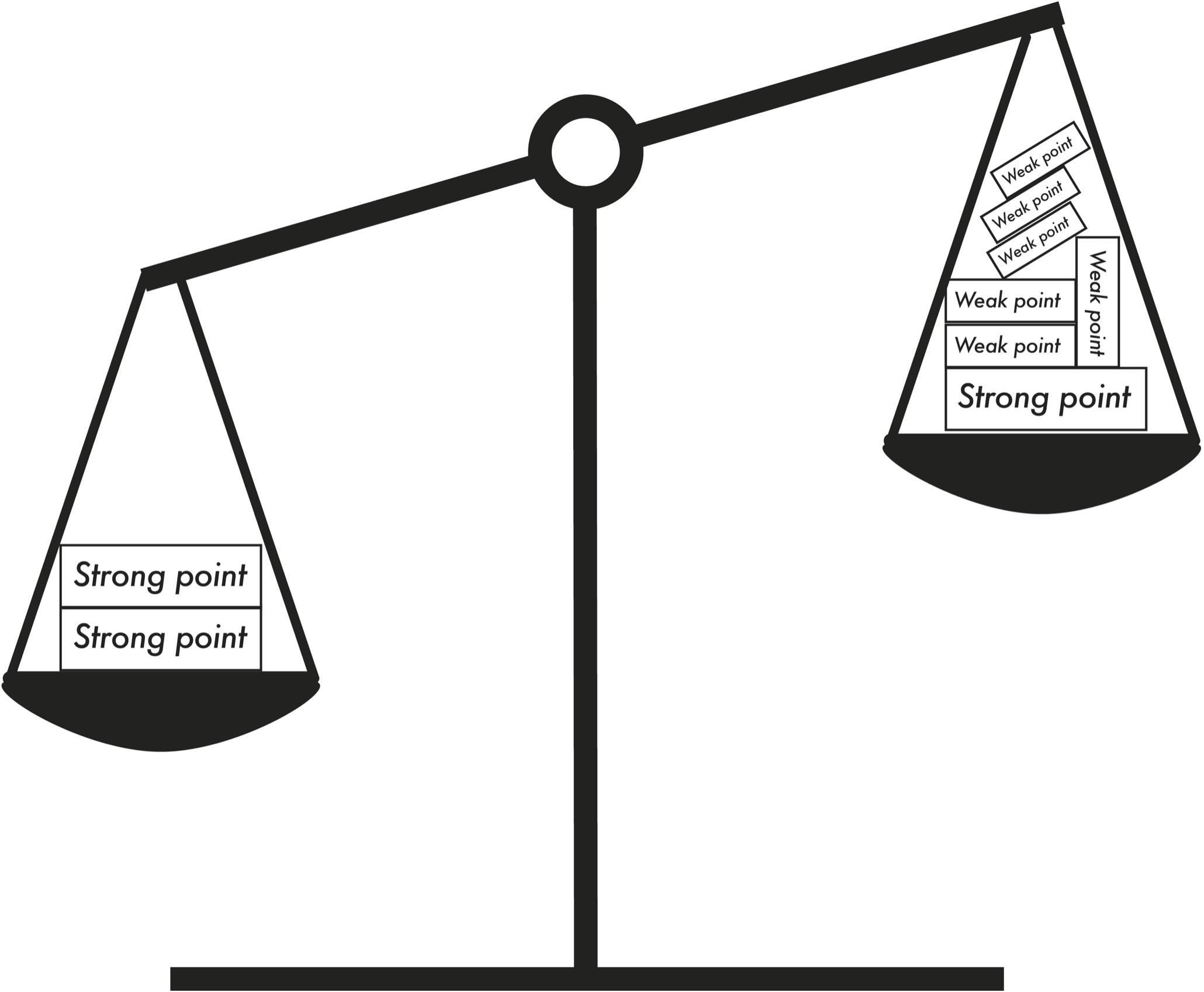

🪺 Don't put all your argument eggs in one basket, the weakest one will be used to judge your more sound arguments.

The more reasons we put on the table, the easier it is for people to discard the shakiest one. Once they reject one of our justifications, they can easily dismiss our entire case. That happened regularly to the average negotiators: they brought too many different weapons to battle. They lost ground not because of the strength of their most compelling point, but because of the weakness of their least compelling one.

Recent experiments show that having even one negotiator who brings a scientist’s level of humility and curiosity improves outcomes for both parties, because she will search for more information and discover ways to make both sides better off. She isn’t telling her counterparts what to think. She’s asking them to dance

🎵 DANCING TO THE SAME BEAT

🦾 Use steel man arguments to strengthen your opponent's weak case. Not only does this show that you're listening, but that you're willing to work together to make both sides come to common ground.

Most people immediately start with a straw man, poking holes in the weakest version of the other side’s case. He does the reverse: he considers the strongest version of their case, which is known as the steel man.

Use a source that your audience connects with well

As important as the quantity and quality of reasons might be, the source matters, too. And the most convincing source is often the one closest to your audience

🧌 DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOSTILE

People have different standards that'll change their minds, so make sure you establish what would change their minds instead of coming up with arguments you assume would change everyone's minds.

Instead of attacking their beliefs with my research, I’d ask them what would open their minds to my data

You can have a conversation about the conversation, maintaining calmness and discussing ways to carry forward with the dialogue.

When someone becomes hostile, if you respond by viewing the argument as a war, you can either attack or retreat. If instead you treat it as a dance, you have another option—you can sidestep. Having a conversation about the conversation shifts attention away from the substance of the disagreement and toward the process for having a dialogue. The more anger and hostility the other person expresses, the more curiosity and interest you show. When someone is losing control, your tranquility is a sign of strength

Do not debate with people who say "nothing" will change their mind.

In a heated argument, you can always stop and ask, “What evidence would change your mind?” If the answer is “nothing,” then there’s no point in continuing the debate. You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it think.

Having a weak opinion but with high emotional conviction will make you lose.

If we hold an opinion weakly, expressing it strongly can backfire

Showing humility by admitting uncertainty makes you sound more credible.

Research shows that in courtrooms, expert witnesses and deliberating jurors are more credible and more persuasive when they express moderate confidence, rather than high or low confidence

people are more interested in hiring candidates who acknowledge legitimate weaknesses as opposed to bragging or humblebragging

Acknowledging and addressing holes in your argument is a sign that you are cognizant of areas that still need more information or learning which credits you as being a "human being" rather than a bragger and a know-it-all.

An informed audience is going to spot the holes in our case anyway. We might as well get credit for having the humility to look for them, the foresight to spot them, and the integrity to acknowledge them

FITTING IN AND STANDING OUT

When someone holds views (regardless of validity) with a group of people sharing those beliefs, the belief becomes more extreme --> called "group polarization".

ENTERING A PARALLEL UNIVERSE

Ask the opponent a what-if scenario with roles switched. If they won't budge, use evidence of that what-if scenario that has happened in real life.

Our role is to hold up a mirror so they can see themselves more clearly, and then empower them to examine their beliefs and behaviors*.* That can activate a rethinking cycle, in which people approach their own views more scientifically. They develop more humility about their knowledge, doubt in their convictions, and curiosity about alternative points of view

Show affirmation or respect of the other side regardless of the choice they make, it could turn out to change their mind even a little bit!

The process of motivational interviewing involves three key techniques:

• Asking open-ended questions

• Engaging in reflective listening

• Affirming the person’s desire and ability to change

A key turning point, she recalls, was when Arnaud “told me that whether I chose to vaccinate or not, he respected my decision as someone who wanted the best for my kids. Just that sentence—to me, it was worth all the gold in the world.”

People will sometimes ignore advice because they feel that they are not in control of their own choices. So frame it as "Here are a few things that have helped me, do you think any of them would work for you?

When we try to convince people to think again, our first instinct is usually to start talking. Yet the most effective way to help others open their minds is often to listen.

THE ART OF INFLUENTIAL LISTENING

👂Often the most successful negotiators listen the most.

We’re all vulnerable to the “righting reflex,” as Miller and Rollnick describe it—the desire to fix problems and offer answers. A skilled motivational interviewer resists the righting reflex—although people want a doctor to fix their broken bones, when it comes to the problems in their heads, they often want sympathy rather than solutions.

🔧 So don't immediately try to fix some problem or issue in an argument, listen first!

Psychologists recommend practicing this skill by sitting down with people whom we sometimes have a hard time understanding. The idea is to tell them that we’re working on being better listeners, we’d like to hear their thoughts, and we’ll listen for a few minutes before responding.

🧠 Leave your listener feeling smarter rather than yourself trying to look smart.

Many communicators try to make themselves look smart. Great listeners are more interested in making their audiences feel smart. They help people approach their own views with more humility, doubt, and curiosity. When people have a chance to express themselves out loud, they often discover new thoughts.

Depolarizing Our Divided Discussions

Opinions are held on a spectrum, they're not binary; and people shouldn't be divided as such. So don't use "us and them" phraseology!

Hearing an opposing opinion doesn’t necessarily motivate you to rethink your own stance; it makes it easier for you to stick to your guns (or your gun bans). Presenting two extremes isn’t the solution; it’s part of the polarization problem.

Psychologists have a name for this: binary bias. It’s a basic human tendency to seek clarity and closure by simplifying a complex continuum into two categories. To paraphrase the humorist Robert Benchley, there are two kinds of people: those who divide the world into two kinds of people, and those who don’t

Don't use clickbait titles, a little bit of humility makes your argument sound like it has more substance.

This applies when we’re the ones producing and communicating information, too. New research suggests that when journalists acknowledge the uncertainties around facts on complex issues like climate change and immigration, it doesn’t undermine their readers’ trust. And multiple experiments have shown that when experts express doubt, they become more persuasive. When someone knowledgeable admits uncertainty, it surprises people, and they end up paying more attention to the substance of the argument.

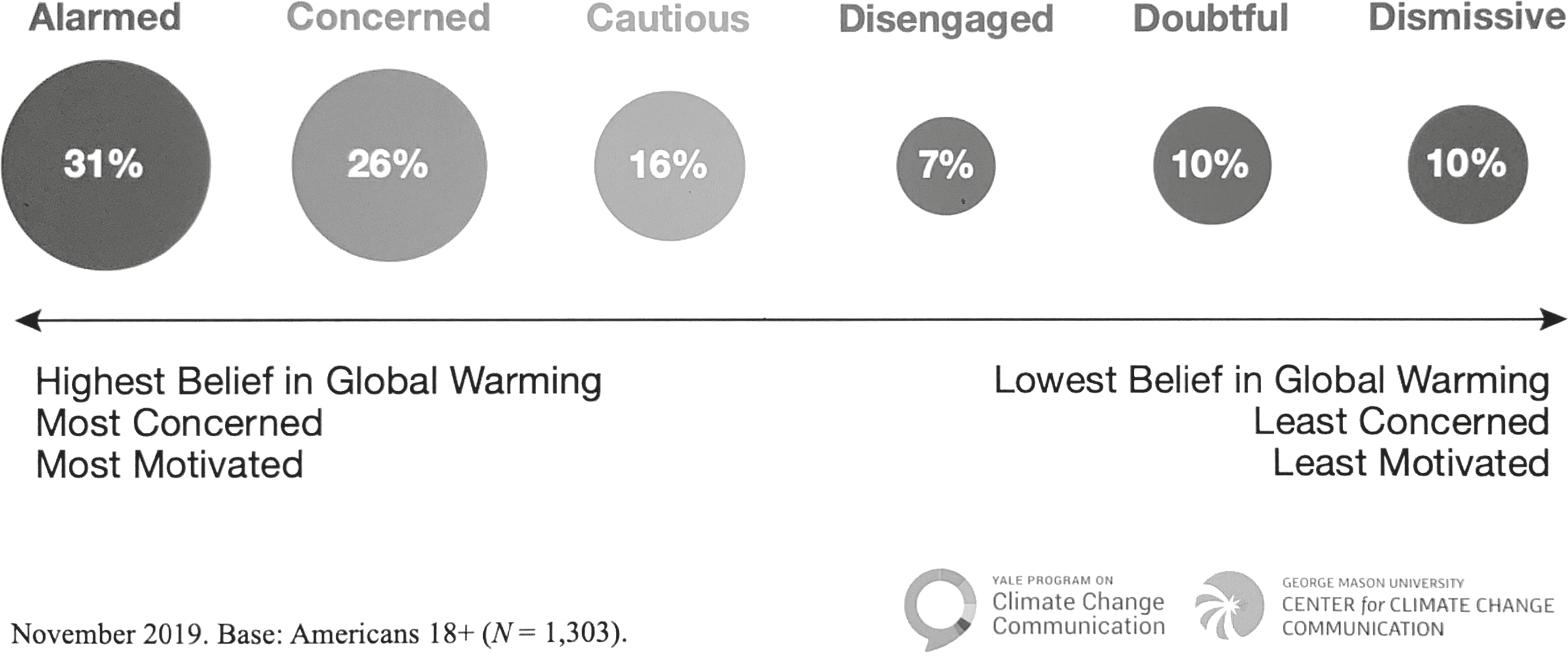

The actionability of solutions to issues is more convincing than doomsday-speak

Psychologists find that people will ignore or even deny the existence of a problem if they’re not fond of the solution. Liberals were more dismissive of the issue of intruder violence when they read an argument that strict gun control laws could make it difficult for homeowners to protect themselves. Conservatives were more receptive to climate science when they read about a green technology policy proposal than about an emissions restriction proposal.

MIXED FEELINGS

Don't assume what people are thinking, strike up a conversation and get a feel for their beliefs through that

THE DUMBSTRUCK EFFECT

As a teacher or coach, Use active learning methods, not passive lecture methods (regardless of how entertaining you are).

Active learning has impact [...] A meta-analysis compared the effects of lecturing and active learning on students’ mastery of the material, cumulating 225 studies with over 46,000 undergraduates in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Active-learning methods included group problem solving, worksheets, and tutorials. On average, students scored half a letter grade worse under traditional lecturing than through active learning—and students were 1.55 times more likely to fail in classes with traditional lecturing. The researchers estimate that if the students who failed in lecture courses had participated in active learning, more than $3.5 million in tuition could have been saved.

Lectures aren’t designed to accommodate dialogue or disagreement; they turn students into passive receivers of information rather than active thinkers. In the above meta-analysis, lecturing was especially ineffective in debunking known misconceptions—in leading students to think again. And experiments have shown that when a speaker delivers an inspiring message, the audience scrutinizes the material less carefully and forgets more of the content—even while claiming to remember more of it

JACK OF ROUGH DRAFTS, MASTER OF CRAFTS

Have students "reinvent the wheel" for some domain of knowledge. Let them do it their own way, do not rush in to fix anything. The point is to start their curiosity engines.

Ron wanted his students to experience the joy of discovery, so he didn’t start by teaching them established knowledge. He began the school year by presenting them with “grapples”—problems to work through in phases. The approach was think-pair-share: the kids started individually, updated their ideas in small groups, and then presented their thoughts to the rest of the class, arriving at solutions together. Instead of introducing existing taxonomies of animals, for example, Ron had them develop their own categories first. Some students classified animals by whether they walked on land, swam in water, or flew through the air; others arranged them according to color, size, or diet. The lesson was that scientists always have many options, and their frameworks are useful in some ways but arbitrary in others

If you want to tell students to "do this X times", say "do this but make X different versions". This will prevent them from thinking that the first draft is supposed to be perfect and totally open them up with multiple possibilities of being able to finish a project. Avoiding tunnel vision, so to speak.

For architecture and engineering lessons, Ron had his students create blueprints for a house. When he required them to do at least four different drafts, other teachers warned him that younger students would become discouraged. Ron disagreed—he had already tested the concept with kindergarteners and first graders in art. Rather than asking them to simply draw a house, he announced, “We’ll be doing four different versions of a drawing of a house.”

SAFE AT HOME GATES

Model and praise exemplary behaviour.

The existing evidence on creating psychological safety gave us some starting points. I knew that changing the culture of an entire organization is daunting, while changing the culture of a team is more feasible. It starts with modeling the values we want to promote, identifying and praising others who exemplify them, and building a coalition of colleagues who are committed to making the change.

When managers admit imperfections, employees will feel more ready to share feedback.

By admitting some of their imperfections out loud, managers demonstrated that they could take it—and made a public commitment to remain open to feedback. They normalized vulnerability, making their teams more comfortable opening up about their own struggles. Their employees gave more useful feedback because they knew where their managers were working to grow. That motivated managers to create practices to keep the door open: they started holding “ask me anything” coffee chats, opening weekly one-on-one meetings by asking for constructive criticism, and setting up monthly team sessions where everyone shared their development goals and progress.

At first, "being open" may be met with skepticism but doing it over time can make the manager more trustworthy for receiving feedback.

Creating psychological safety can’t be an isolated episode or a task to check off on a to-do list. When discussing their weaknesses, many of the managers in our experiment felt awkward and anxious at first. Many of their team members were surprised by that vulnerability and unsure of how to respond. Some were skeptical: they thought their managers might be fishing for compliments or cherry-picking comments that made them look good. It was only over time—as managers repeatedly demonstrated humility and curiosity—that the dynamic changed.

THE WORST THING ABOUT BEST PRACTICES

Praising and rewarding results can create a false sense of security and prevent people from questioning their practices until something goes wrong.

Sure enough, social scientists find that when people are held accountable only for whether the outcome was a success or failure, they are more likely to continue with ill-fated courses of action. Exclusively praising and rewarding results is dangerous because it breeds overconfidence in poor strategies, incentivizing people to keep doing things the way they’ve always done them. It isn’t until a high-stakes decision goes horribly wrong that people pause to reexamine their practices.

Use process accountability, and explain procedures in real-time to avoid getting the right result but more on focusing on getting the right result the right way

Research shows that when we have to explain the procedures behind our decisions in real time, we think more critically and process the possibilities more thoroughly.

In learning cultures, people don’t stop keeping score. They expand the scorecard to consider processes as well as outcomes

Reconsidering Our Best-Laid Career and Life Plans

Don't ask the question "what do you want to be" to a child. They have no idea what's out there, and they probably don't have the notion that they could choose their own path in life. They'll lock themselves into that position for the next decade or two out of moral guilt, not knowing they could have changed paths.

We all have notions of who we want to be and how we hope to lead our lives. They’re not limited to careers; from an early age, we develop ideas about where we’ll live, which school we’ll attend, what kind of person we’ll marry, and how many kids we’ll have. These images can inspire us to set bolder goals and guide us toward a path to achieve them. The danger of these plans is that they can give us tunnel vision, blinding us to alternative possibilities. We don’t know how time and circumstances will change what we want and even who we want to be, and locking our life GPS onto a single target can give us the right directions to the wrong destination.

GOING INTO FORECLOSURE

Don't succumb to the sunken cost fallacy by escalating your level of commitment. Just because you have already put in so much time or effort, it doesn't mean it's going to be productive for you in the long term. Doubling down on some obviously failing matters could be detrimental to you!

When we dedicate ourselves to a plan and it isn’t going as we hoped, our first instinct isn’t usually to rethink it. Instead, we tend to double down and sink more resources in the plan. This pattern is called escalation of commitment

Evidence shows that entrepreneurs persist with failing strategies when they should pivot, NBA general managers and coaches keep investing in new contracts and more playing time for draft busts, and politicians continue sending soldiers to wars that didn’t need to be fought in the first place. Sunk costs are a factor, but the most important causes appear to be psychological rather than economic

Escalation of commitment happens because we’re rationalizing creatures, constantly searching for self-justifications for our prior beliefs as a way to soothe our egos, shield our images, and validate our past decisions.

Member discussion